The Navy Conundrum

Every military branch is preparing to face China in the Western Pacific. The directives for the Air Force and Army are relatively clear. The Air Force needs to keep its bases running and its planes from getting destroyed on the ground. Some combination of dispersal bases, hardening, and active defenses is the answer. The Army needs better missile defenses (it provides ground-based air defense at Air Force bases) and short-range air defenses to counter drones.

The Navy is different. Uncertainty is much higher, and the service is muddling through, mostly maintaining the status quo. Many of its recent shipbuilding programs have been disasters (Ford, Zumwalt, LCS). Part of the issue is that there hasn't been a significant naval battle for 80 years, and there have been no real challenges to the US Navy until recently. Armies and Air Forces have had Korea, Vietnam, the Israeli-Arab wars, and two wars in Iraq to showcase changes in warfare. The advances in naval warfare have been theoretical outside of a few engagements clustered in the 1980s where anti-ship missiles tussled with lower-tier ships.

Instead of trying to speculate on what would be the perfect Navy, I'm going to guess how we might rapidly augment a few capabilities that would be in high demand during a conflict with China. I've mentioned many of these in other posts but will go into more detail here.

Setting the Strategic Framework

A recently published war game simulating a Chinese invasion of Taiwan provided food for thought. War games aren't real life, but that doesn't mean we can't learn from them, especially one that alters assumptions to see the direction and magnitude of change. War games are like setting a point spread for a football game. They guess a median outcome without addressing the messy tail events that happen during an event. Some notable opinons:

-

Improve Land-Based Airpower

Some of the most favorable changes for the US were the ability to use all of Japan's airports and the hardening of existing bases from missile attacks. Fewer planes died on the ground, and tactical airpower helped whittle down Chinese shipping, leaving the invasion force without support. Base hardening is expensive, and the Air Force has focused on the most critical projects like standing up dispersal fields, hardening fuel infrastructure, and building shelters for maintenance equipment. Pricier upgrades like hardened aircraft shelters aren't a priority. They prefer to buy new planes or work on their next-generation fighter.

Hardened aircraft shelters started simple and cheap during Vietnam as emergency protection from rockets. They have grown into sophisticated buildings with extensive features. But basic will come back in style if war becomes imminent. The construction operation in Vietnam could complete almost a shelter a day at its peak, with each coming in at $200,000 in 2023 dollars.

-

Anti-ship Missiles Hurt China More

One of the most contentious assumptions is how vulnerable ships are to anti-ship missiles. The more vulnerable ships were, the worse China performed. US naval forces can stay relatively far away from China. But China has to constantly have ships crossing the Taiwan Strait to support its invasion. There is always the possibility that China's missile defenses are much better, but typically we underestimate the capabilities of open democracies and overestimate totalitarian regimes. The US Navy surface fleet will cease to be relevant if there is a gap and it doesn't learn fast.

-

Taiwan's Army Has to Fight

Taiwan did not stop an initial landing of Chinese troops, even with many varying assumptions. The Taiwan Strait is only 100-200 km across. Time is short and Chinese ships are numerous during an invasion. The outcome probably looks more like Ukraine losing Crimea if the Taiwanese Army collapses. The US will move on with a minor response. We can only deploy our forces and influence the fight if the Taiwanese fight hard.

The Japan Question

Japan's participation is critical to any US defense of Taiwan. A dozen potential airfields are available on Okinawa and other Japanese islands - the closest is only 120 km from Taiwan. Naval aircraft can fly from these land bases if carriers aren't available. There are also bases in the Philippines, but they are not as well positioned as the Japanese airfields. Whether Japan will fight is an important question.

Japan may not have a choice. Many of China's military thought leaders favor a first strike on US bases in the region, many of which are in Japan. You can't discount Chinese landings on the lightly populated islands closest to Taiwan.

Taiwan keeps China bottled up and out of the wider Pacific. Japan would be extremely isolated and at the mercy of China if Taiwan fell. They remember nearly starving due to US submarines and mines in World War II. Japan's best chance to maintain their current level of autonomy is to fight with the US to defend Taiwan and themselves. Their rapidly increasing military budget supports this line of reasoning.

The Navy's Role in East Asia

The Navy's minimum role collapses and simplifies when we combine the strategic factors. Carriers get all the attention, but the Navy can rely on land-based air cover from its planes and the Air Force when the battlefield is a confined space like Taiwan. Supply lines to these bases and our allies are still critical. Several objectives emerge:

-

Maintain supply lines to island airfields

Tactical aircraft need fuel, parts, bombs, and missiles.

-

Reopen sea lanes to Eastern Taiwan

Taiwan will wither and starve without deliveries of food and ammunition.

-

Improve submarine access to Chinese waters

US Navy submarines are an alternative to missiles for putting pressure on Chinese shipping.

How the US Navy Can Achieve These Objectives

The two primary obstacles to these objectives are mines and diesel-electric submarines.

Surface vessels are less of a concern to supply lines. The Chinese Navy often deploys ships on the east side of Taiwan during exercises, but they are more exposed, and the ocean depth is favorable for the US. Attack submarines, bombers, fighters, and surface vessels are all available to attack.

US Supply lines can operate under land-based air cover and missile defense along the Ryukyu Islands. The best ways for the Chinese to disrupt these supply chains are mines and submarines.

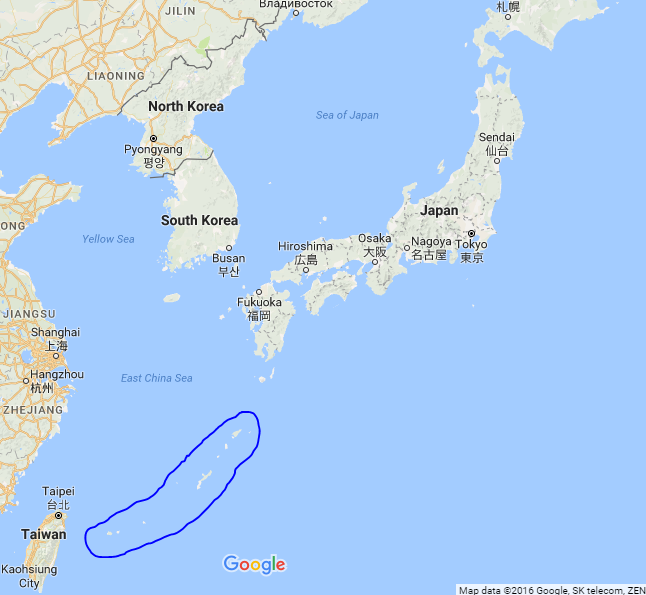

The Ryukyu Islands are Unsinkable Aircraft Carriers Source

The US will only suffer a shortage of tactical airpower if we lose our carriers AND can't access Japanese airfields AND lose access to basing rights in the Philippines AND still want to fight. If Taiwan only spends 2% of its GDP on its military while Japan and the Philippines want to be "neutral," why should the US fight for them from a terrible strategic position? We might, but we can always contain China's further expansion from the second island chain, where our advantage is still decisive.

Mines and submarines!

Minesweepers

China might have 100,000 naval mines they can deploy from fishing boats, submarines, ships, or aircraft. These mines could keep US ships and submarines from operating in the shallow waters surrounding Taiwan, prevent the resupply of Taiwanese armed forces, and hinder US operations by covertly mining key points around Okinawa or Guam. Mines caused problems for the US Navy in Korea and the First Gulf War. The Chinese hope for similar success if a war erupts.

The US Navy has eight aging minesweepers. Four are in Japan, vulnerable to a Chinese first strike. The other four are in the Persian Gulf. It also has a few tired helicopters that pull sleds. The Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) was supposed to take over from these aging platforms, but it has been a complete failure.

There are two ways to counter mines - sweeping or hunting. Mine sweeping is fast but imprecise and usually involves triggering mines by imitating ships. It does not locate individual mines, and some can be left. Hunting mines means deliberately searching for every mine and destroying them. It is thorough but painfully slow. Advances in mines hurt the effectiveness of sweeping because the mines don't fall for simple decoy signals meant to trigger them. Some mines can attack specific classes of ships based on their unique signature. Many mines are now bottom-dwelling to make detection challenging and prevent sweepers from breaking their moors with heavy lines. Most of the Navy's recent focus has been on mine hunting due to the challenges of sweeping. But sweeping might come back in fashion if tens of thousands of mines cover every key chokepoint.

Minesweepers are made out of wood and fiberglass when there is time to spare. These materials make the ship less likely to trigger mines. But there is a history of using steel or converting existing ships (civilian or military) to minesweepers in emergencies. There are several features these ships might have:

-

Sonar to Find Mines

Most minesweepers have active sonar arrays to find potential mines. There are low-resolution modes for broad searches and high-resolution modes for investigating potential mines. The Navy might have to adapt less capable off-the-shelf sonar and put those arrays on whatever ships they can scrap together.

-

Charges to Destroy Mines

A brute force option might be launching depth charges at anything that looks like a mine on wide-view sonar rather than confirming with narrow-band sonar, UUVs, or divers.

-

Better Mine Triggering Methods

It would be ideal if new decoys could simulate ship sounds and magnetic signatures well enough to trigger mines.

-

Underwater Micro Drones

Some proposals envision launching small unmanned underwater vehicles from motherships to seek out mines and eliminate them - essentially underwater loitering munitions. These are one of the few technologies that might help US submarines fight in the shallows deep in Chinese territory.

Minesweeping capability will be critical for supplying forward bases, keeping Taiwan from starving, and gaining entry to the Taiwan Strait later in the conflict. The fastest capabilities will be converting existing vessels by outfitting them with sonar and simple ways to launch charges at suspected mines. Micro UUVs and synthetic mine triggers should be crash R+D programs since they could dramatically improve effectiveness.

Submarine Tracking

The People's Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has numerous short-range diesel-electric submarines that excel at fighting in shallow waters. They are quiet and hard to find when they operate in battery mode. Many US sonars work better in deep water, compounding the diesel sub advantage. Their slow electric speed (<3 knots to avoid running down the battery) is a disadvantage but matters less when operating in shallow choke points. Many of these subs will be laying mines, making it even more critical to neutralize them. Finding the submarines is the hard part. The US may not have air supremacy, so the answer can't be P-8 patrol planes dropping buoys at every likely hiding place. There are a few options:

-

More Advanced Listening Network

The US tracked Russian nuclear submarines during the Cold War with a network of sensors in the Deep Sound Channel that transports noises for hundreds or thousands of miles. Most waters in East Asia are too shallow for this layer to exist. A network in East Asia will need more nodes or different technology to work effectively.

These capabilities are highly classified, and there have been suggestions that the US and Japan are improving the existing systems. The Navy has also added low-frequency active sonar with a 160+ km range to their submarine tracking boats. These systems perform much better against quiet diesel subs in shallow water.

China has also built listening networks to counter US submarines.

-

Underwater Seagliders

Seagliders and wave gliders are a class of drones that loiter in the ocean for months or years to collect data. They are hyper-efficient, often using a few watts. The mission can be as simple as collecting oceanographic data or as complex as tracking enemy subs. These gliders could increase submarine detection capability deep in enemy territory. They have to prove that they are stealthy enough to avoid detection/destruction, and software must be energy efficient to avoid running down the batteries.

-

Expendable Drone Aircraft

Another speculative option is putting sensors like magnetic anomaly detectors (MAD) on small, inexpensive flying drones. You might be able to buy hundreds of these for the cost of one anti-submarine warfare (ASW) helicopter, increasing the coverage area.

-

ASW Patrol Boats

There won't be time to build anti-submarine warfare powerhouses like a Perry-class frigate or Spruance-class destroyer. And the current fleet has no dedicated ASW ship. There will be a need for boats capable of escorting carrier battle groups and convoys. The more desperate the timeline, the more ramshackle solutions will be. Grafting on older sonar arrays and torpedo racks is probably the bare minimum.

China's submarines hope to disrupt US Navy access to the waters around China and Taiwan. The US will have to locate them. A new listening network optimized for East Asia is the best and most reliable option, while drone capabilities might supplement them as technology improves.

Turning the Tables

Our three objectives get increasingly challenging. It is easier to build listening networks or clear harbors of mines in the Ryukyu Islands than in Taiwan. Even harder is locating submarines and eliminating mines in enemy territory. But operating closer to China opens opportunities for the Navy to threaten the Chinese invasion independent of carriers, airfields, Air Force bombers, or long-range missiles.

Offensive and Defensive Mines

Anti-ship mines could be as dangerous (if not more) for the People's Liberation Army as the US and its allies. Taiwan has few beaches and ports suitable for amphibious invasion, making Chinese movements predictable. Hundreds of kilometers of shallow water that are ideal for mines surround China. They are a chaos-inducing weapon because they could delay or destroy Chinese ships, allowing Taiwan to mobilize its military. Mines could also be a way for the US to support Taiwan without committing to a full intervention.

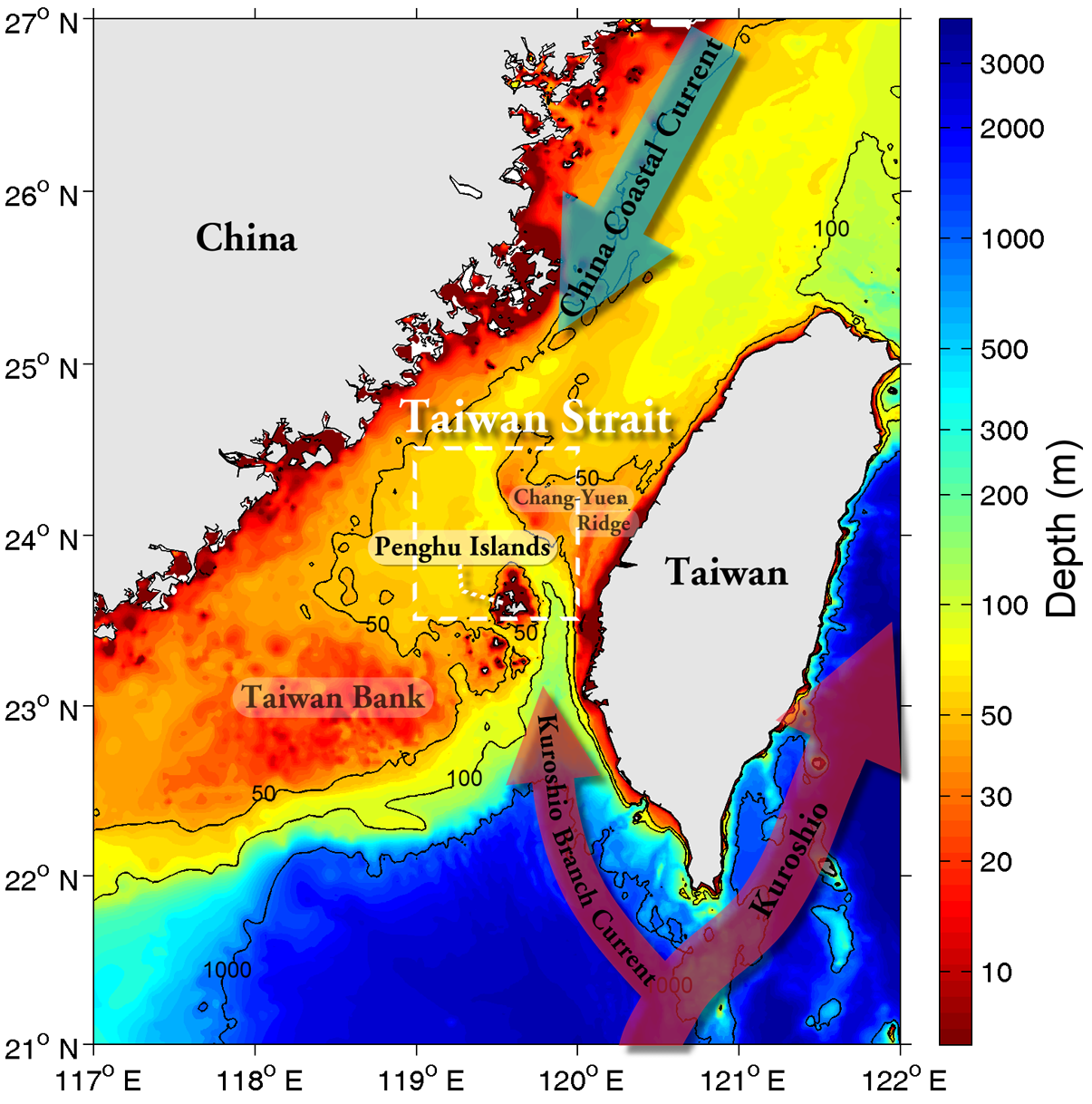

Shallow water! Source

Unfortunately, the US has neglected mines until the last few years. Its inventory (~10,000 mines?) is inadequate and new models are not fully operational. There is also a minelaying capacity issue. Nuclear attack submarines can only carry 20-50 mines. B-1 and B-52 bombers can carry up to 80 smaller mines but may be too valuable and vulnerable to sortie on minelaying. B-2 stealth bombers do not even train for mine-laying missions. Rapid deployment matters because minefields often need thousands of mines to be effective.

There are a few initiatives to correct these issues:

-

Quickstrike Mines

The Navy recently upgraded its Quickstrike air-launched mine family with modern sensors. These shallow-water mines are conventional bombs with fuses swapped for the mine sensors. The appeal of the Quickstrike mines is that they benefit from air-dropped bomb economies of scale and scope. The cost is low, and manufacturing can ramp quickly. JDAM guidance packages allow aircraft to launch mines from 80 kilometers away. Previously, aircraft had to fly low and slow over the minefield, making them easy targets.

The Air Force may not want to risk its bombers to lay mines, but it might be willing to risk C-130 cargo planes. The Rapid Dragon program is giving them the ability to drop JDAM-equipped bombs. There are enough C-130s to lay entire minefields in one mission, helping to justify the aircraft package of fighters and electronic warfare aircraft required to get the cargo aircraft close enough to drop the mines. There is still a limit to where the Navy and Air Force can realistically deploy these weapons.

-

Clandestine Delivered Mine

Submarines can deploy mines closer to enemy shores and ports than aircraft. The Navy is upgrading its obsolete submarine mines with the CDM. There are no details about its abilities or operational status.

-

Hammerhead Mine

Increasing the range that a mine can kill a ship or sub reduces how many mines the Navy needs to lay. The Hammerhead Mine is a system that fires a torpedo at targets, extending its range from meters to kilometers. They would help alleviate the submarine minelaying constraint. The program could reach operational status within the next few years, but rumors suggest production is only thirty units per year. That is not enough to move the needle!

-

Programmable Mines

Mines used to be indiscriminate. Now they can decipher what kind of ship they are attacking. The next step is to lay them in a dormant state and only activate them at the start of hostilities. Fewer platforms can place mines before a conflict erupts. The Navy has shown interest in this capability, but no known programs are pursuing it.

Mines hold incredible potential for the US Navy, but every initiative needs a 10x multiplier.

Unleashing US Attack Submarines

US attack submarines are feared worldwide. They could wreak havoc on Chinese shipping with torpedos, anti-ship missiles, and mines. But we don't have enough of them. The US Navy deployed ~250 submarines in World War II. The force had little impact before focusing on chokepoints like the Taiwan Strait. The submarine density was too low before the strategy change. The Navy has ~50 attack submarines today. They are more capable but struggle to fulfill all their missions like mine laying, strike, tracking enemy missile submarines, surveillance, and disrupting enemy shipping. And deploying them in shallow water filled with diesel submarines and mines is no one's idea of fun.

The Navy needs previously discussed improvements to minesweeping and submarine detection to reduce the risk of operating subs in Chinese waters. Better weapons can also help submarine survivability. The harpoon missile and Mk-48 torpedos are undergoing incremental upgrades. Torpedos can always be quieter at the start (to avoid giving away the sub's position), faster in the final sprint toward the target, and better at targeting.

The US Navy also needs more submarines if it is serious about minelaying. The Navy and its suppliers seem hesitant to expand production beyond the two shipyards capable of building the beasts. The construction of the new Columbia class nuclear missile submarines further strains the system. Instead, the Navy wants the Orca Extra Large Unmanned Underwater Vehicle (XLUUV). On paper, these are the perfect solution for laying mines. Each copy is supposed to cost less than $50 million and operates without crew, allowing more risk in their mission profile. Their smaller size and lower complexity mean manufacturing time can be short and take place in many shipyards. The program started with high hopes and a successful prototype but is now three years late and hundreds of millions over budget to deliver the first production model. The Navy bought five Orca subs and hopes to have them by the end of 2024.

Energy and payload are related issues when examining the XLUUV mission closer. These subs have diesel-electric powertrains, making them very slow.[1] A round trip to lay mines might take ten days, and they carry fewer mines than a traditional submarine. Even advanced mines like Hammerhead might require 50-100 XLUUVs to be effective. Anduril's Dive LD subsidy could provide some competition and claims costs as low as $30 million per XLUUV. They are still in the honeymoon prototype stage and don't expect the first production version until 2025 (delivered to the Australian Navy). Another option would be to bite the bullet and outfit a few Virginia class subs as dedicated minelayers that can carry 2x-3x the typical payload. It'd take ~40 XLUUVs to match the capacity of one Virginia class minelayer. Manufacturing will have to improve significantly to make XLUUVs practical, and the Navy might still want to convert an existing design to a dedicated minelayer.

The Offensive Summary

$5 billion to buy mines and covert minelayers would create a world-class mine capability and delivery system while freeing up attack subs to put ships on the bottom.

Expanding The Navy's Influence

The purpose of a Navy is to influence events on land. The US Navy's direct impact on land battles will be relatively fleeting except for its aircraft. It has more vertical launch tubes than land attack missiles. Missiles like the Tomahawk aren't ideal weapons for attacking infantry divisions, and many are being converted to anti-ship missiles since Navy cruisers and destroyers have limited organic anti-ship capability. Modern ships have very few guns to bombard land targets with.

The way to impact land battles is fire support with heavier guns.[2] The Navy conducted fire missions in World War II, Korea, Vietnam, and Desert Storm using the 8" and 16" guns on its heavy cruisers and battleships. The firepower of four Iowa class ships would equal ~20% of Taiwan's tube artillery capability and nearly 100% of its highest-performance pieces, even with subcaliber 180-kilometer range shells. Adding modern heavy cruisers would allow the Navy to bring an army worth of artillery to bear for US allies, complete with an efficient seaborne supply chain.

Regaining fire support capability requires a different Navy. It must improve ship procurement and design to avoid disasters like Ford, LCS, and Zumwalt. Ships need some ability to absorb missile hits. Overall, the warships need to be simpler and more specialized. Not every class needs a giant radar or helicopters! These changes will free up the resources to build ships that widen the Navy's capabilities.

The Minimum Viable Navy

The Navy surface fleet is essentially floating airstrips surrounded by air defense batteries. There is only room for ships devoted to carrier operations at today's aircraft carrier costs. Floating airfields are valuable where land bases are constrained or surprise/mobility is critical.

Potential flashpoints with China, like Taiwan or the South China Sea, are more expansive than Europe but aren't the vast Central Pacific. Airfields, aircraft, land-based air defense, and small utility ships can replicate most of a carrier strike group's capabilities in a war with China. Aircraft are capable anti-ship platforms, they can keep enemy airplanes at bay, and there are plenty of airfields to fly from. But they cannot clear the way for supply ships nor operate persistently deep in enemy territory. The minimum viable Navy has to handle enemy mines and submarines. Adding offensive mine and submarine capabilities is the next logical step.

To have more than the minimum navy capability, the US must change how it procures ships, improve the productivity of its shipbuilding industry, and have coherent goals. Carriers can't and shouldn't cost $15 billion, and the weapons and platforms must work.[3] More reasonable carrier costs would allow the fleet to increase in size and add tools to the toolbox. The Navy is just safeguarding the Air Force's packages until then!

-

The Navy needs a nuclear nano-reactor startup to pivot to small submarine propulsion (manned or unmanned). Having faster small subs with more range would decrease how many need to be purchased compared to a diesel-electric powertrain and could take more load off traditional nuclear attack submarines in domains like intelligence gathering. KRUSTY for subs!

-

Naval guns vs. rockets like HIMARS fires are a common debate. Ships are great at carrying big, heavy things like giant gun barrels. But it is difficult for them to store and transport lengthy ammunition throughout the ship. That makes guns a good choice. The Navy has used rockets on ships like the LSM-R before they designed their own rockets to have similar dimensions to traditional shells instead of long, skinny Army rockets.

-

The Forrestal class carriers had similar capabilities to today's carriers but cost <$2.5 billion inflation adjusted dollars. The improved Kitty Hawk class also cost around $2.5 billion in 2022 dollars. Global commercial ship prices have risen slower than CPI inflation over the same time period.

-

Much of the background for this post was influenced by the Naval Matters Blog. Again, there are few other places like it to learn about and speculate on modern naval warfare.

The Minimum Viable Navy

2023 May 22 Twitter Substack See all postsWhat is the absolute minimum performance we need to counter China?

The Navy Conundrum

Every military branch is preparing to face China in the Western Pacific. The directives for the Air Force and Army are relatively clear. The Air Force needs to keep its bases running and its planes from getting destroyed on the ground. Some combination of dispersal bases, hardening, and active defenses is the answer. The Army needs better missile defenses (it provides ground-based air defense at Air Force bases) and short-range air defenses to counter drones.

The Navy is different. Uncertainty is much higher, and the service is muddling through, mostly maintaining the status quo. Many of its recent shipbuilding programs have been disasters (Ford, Zumwalt, LCS). Part of the issue is that there hasn't been a significant naval battle for 80 years, and there have been no real challenges to the US Navy until recently. Armies and Air Forces have had Korea, Vietnam, the Israeli-Arab wars, and two wars in Iraq to showcase changes in warfare. The advances in naval warfare have been theoretical outside of a few engagements clustered in the 1980s where anti-ship missiles tussled with lower-tier ships.

Instead of trying to speculate on what would be the perfect Navy, I'm going to guess how we might rapidly augment a few capabilities that would be in high demand during a conflict with China. I've mentioned many of these in other posts but will go into more detail here.

Setting the Strategic Framework

A recently published war game simulating a Chinese invasion of Taiwan provided food for thought. War games aren't real life, but that doesn't mean we can't learn from them, especially one that alters assumptions to see the direction and magnitude of change. War games are like setting a point spread for a football game. They guess a median outcome without addressing the messy tail events that happen during an event. Some notable opinons:

Improve Land-Based Airpower

Some of the most favorable changes for the US were the ability to use all of Japan's airports and the hardening of existing bases from missile attacks. Fewer planes died on the ground, and tactical airpower helped whittle down Chinese shipping, leaving the invasion force without support. Base hardening is expensive, and the Air Force has focused on the most critical projects like standing up dispersal fields, hardening fuel infrastructure, and building shelters for maintenance equipment. Pricier upgrades like hardened aircraft shelters aren't a priority. They prefer to buy new planes or work on their next-generation fighter.

Hardened aircraft shelters started simple and cheap during Vietnam as emergency protection from rockets. They have grown into sophisticated buildings with extensive features. But basic will come back in style if war becomes imminent. The construction operation in Vietnam could complete almost a shelter a day at its peak, with each coming in at $200,000 in 2023 dollars.

Anti-ship Missiles Hurt China More

One of the most contentious assumptions is how vulnerable ships are to anti-ship missiles. The more vulnerable ships were, the worse China performed. US naval forces can stay relatively far away from China. But China has to constantly have ships crossing the Taiwan Strait to support its invasion. There is always the possibility that China's missile defenses are much better, but typically we underestimate the capabilities of open democracies and overestimate totalitarian regimes. The US Navy surface fleet will cease to be relevant if there is a gap and it doesn't learn fast.

Taiwan's Army Has to Fight

Taiwan did not stop an initial landing of Chinese troops, even with many varying assumptions. The Taiwan Strait is only 100-200 km across. Time is short and Chinese ships are numerous during an invasion. The outcome probably looks more like Ukraine losing Crimea if the Taiwanese Army collapses. The US will move on with a minor response. We can only deploy our forces and influence the fight if the Taiwanese fight hard.

The Japan Question

Japan's participation is critical to any US defense of Taiwan. A dozen potential airfields are available on Okinawa and other Japanese islands - the closest is only 120 km from Taiwan. Naval aircraft can fly from these land bases if carriers aren't available. There are also bases in the Philippines, but they are not as well positioned as the Japanese airfields. Whether Japan will fight is an important question.

Japan may not have a choice. Many of China's military thought leaders favor a first strike on US bases in the region, many of which are in Japan. You can't discount Chinese landings on the lightly populated islands closest to Taiwan.

Taiwan keeps China bottled up and out of the wider Pacific. Japan would be extremely isolated and at the mercy of China if Taiwan fell. They remember nearly starving due to US submarines and mines in World War II. Japan's best chance to maintain their current level of autonomy is to fight with the US to defend Taiwan and themselves. Their rapidly increasing military budget supports this line of reasoning.

The Navy's Role in East Asia

The Navy's minimum role collapses and simplifies when we combine the strategic factors. Carriers get all the attention, but the Navy can rely on land-based air cover from its planes and the Air Force when the battlefield is a confined space like Taiwan. Supply lines to these bases and our allies are still critical. Several objectives emerge:

Maintain supply lines to island airfields

Tactical aircraft need fuel, parts, bombs, and missiles.

Reopen sea lanes to Eastern Taiwan

Taiwan will wither and starve without deliveries of food and ammunition.

Improve submarine access to Chinese waters

US Navy submarines are an alternative to missiles for putting pressure on Chinese shipping.

How the US Navy Can Achieve These Objectives

The two primary obstacles to these objectives are mines and diesel-electric submarines.

Surface vessels are less of a concern to supply lines. The Chinese Navy often deploys ships on the east side of Taiwan during exercises, but they are more exposed, and the ocean depth is favorable for the US. Attack submarines, bombers, fighters, and surface vessels are all available to attack.

US Supply lines can operate under land-based air cover and missile defense along the Ryukyu Islands. The best ways for the Chinese to disrupt these supply chains are mines and submarines.

The Ryukyu Islands are Unsinkable Aircraft Carriers Source

The US will only suffer a shortage of tactical airpower if we lose our carriers AND can't access Japanese airfields AND lose access to basing rights in the Philippines AND still want to fight. If Taiwan only spends 2% of its GDP on its military while Japan and the Philippines want to be "neutral," why should the US fight for them from a terrible strategic position? We might, but we can always contain China's further expansion from the second island chain, where our advantage is still decisive.

Mines and submarines!

Minesweepers

China might have 100,000 naval mines they can deploy from fishing boats, submarines, ships, or aircraft. These mines could keep US ships and submarines from operating in the shallow waters surrounding Taiwan, prevent the resupply of Taiwanese armed forces, and hinder US operations by covertly mining key points around Okinawa or Guam. Mines caused problems for the US Navy in Korea and the First Gulf War. The Chinese hope for similar success if a war erupts.

The US Navy has eight aging minesweepers. Four are in Japan, vulnerable to a Chinese first strike. The other four are in the Persian Gulf. It also has a few tired helicopters that pull sleds. The Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) was supposed to take over from these aging platforms, but it has been a complete failure.

There are two ways to counter mines - sweeping or hunting. Mine sweeping is fast but imprecise and usually involves triggering mines by imitating ships. It does not locate individual mines, and some can be left. Hunting mines means deliberately searching for every mine and destroying them. It is thorough but painfully slow. Advances in mines hurt the effectiveness of sweeping because the mines don't fall for simple decoy signals meant to trigger them. Some mines can attack specific classes of ships based on their unique signature. Many mines are now bottom-dwelling to make detection challenging and prevent sweepers from breaking their moors with heavy lines. Most of the Navy's recent focus has been on mine hunting due to the challenges of sweeping. But sweeping might come back in fashion if tens of thousands of mines cover every key chokepoint.

Minesweepers are made out of wood and fiberglass when there is time to spare. These materials make the ship less likely to trigger mines. But there is a history of using steel or converting existing ships (civilian or military) to minesweepers in emergencies. There are several features these ships might have:

Sonar to Find Mines

Most minesweepers have active sonar arrays to find potential mines. There are low-resolution modes for broad searches and high-resolution modes for investigating potential mines. The Navy might have to adapt less capable off-the-shelf sonar and put those arrays on whatever ships they can scrap together.

Charges to Destroy Mines

A brute force option might be launching depth charges at anything that looks like a mine on wide-view sonar rather than confirming with narrow-band sonar, UUVs, or divers.

Better Mine Triggering Methods

It would be ideal if new decoys could simulate ship sounds and magnetic signatures well enough to trigger mines.

Underwater Micro Drones

Some proposals envision launching small unmanned underwater vehicles from motherships to seek out mines and eliminate them - essentially underwater loitering munitions. These are one of the few technologies that might help US submarines fight in the shallows deep in Chinese territory.

Minesweeping capability will be critical for supplying forward bases, keeping Taiwan from starving, and gaining entry to the Taiwan Strait later in the conflict. The fastest capabilities will be converting existing vessels by outfitting them with sonar and simple ways to launch charges at suspected mines. Micro UUVs and synthetic mine triggers should be crash R+D programs since they could dramatically improve effectiveness.

Submarine Tracking

The People's Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has numerous short-range diesel-electric submarines that excel at fighting in shallow waters. They are quiet and hard to find when they operate in battery mode. Many US sonars work better in deep water, compounding the diesel sub advantage. Their slow electric speed (<3 knots to avoid running down the battery) is a disadvantage but matters less when operating in shallow choke points. Many of these subs will be laying mines, making it even more critical to neutralize them. Finding the submarines is the hard part. The US may not have air supremacy, so the answer can't be P-8 patrol planes dropping buoys at every likely hiding place. There are a few options:

More Advanced Listening Network

The US tracked Russian nuclear submarines during the Cold War with a network of sensors in the Deep Sound Channel that transports noises for hundreds or thousands of miles. Most waters in East Asia are too shallow for this layer to exist. A network in East Asia will need more nodes or different technology to work effectively.

These capabilities are highly classified, and there have been suggestions that the US and Japan are improving the existing systems. The Navy has also added low-frequency active sonar with a 160+ km range to their submarine tracking boats. These systems perform much better against quiet diesel subs in shallow water.

China has also built listening networks to counter US submarines.

Underwater Seagliders

Seagliders and wave gliders are a class of drones that loiter in the ocean for months or years to collect data. They are hyper-efficient, often using a few watts. The mission can be as simple as collecting oceanographic data or as complex as tracking enemy subs. These gliders could increase submarine detection capability deep in enemy territory. They have to prove that they are stealthy enough to avoid detection/destruction, and software must be energy efficient to avoid running down the batteries.

Expendable Drone Aircraft

Another speculative option is putting sensors like magnetic anomaly detectors (MAD) on small, inexpensive flying drones. You might be able to buy hundreds of these for the cost of one anti-submarine warfare (ASW) helicopter, increasing the coverage area.

ASW Patrol Boats

There won't be time to build anti-submarine warfare powerhouses like a Perry-class frigate or Spruance-class destroyer. And the current fleet has no dedicated ASW ship. There will be a need for boats capable of escorting carrier battle groups and convoys. The more desperate the timeline, the more ramshackle solutions will be. Grafting on older sonar arrays and torpedo racks is probably the bare minimum.

China's submarines hope to disrupt US Navy access to the waters around China and Taiwan. The US will have to locate them. A new listening network optimized for East Asia is the best and most reliable option, while drone capabilities might supplement them as technology improves.

Turning the Tables

Our three objectives get increasingly challenging. It is easier to build listening networks or clear harbors of mines in the Ryukyu Islands than in Taiwan. Even harder is locating submarines and eliminating mines in enemy territory. But operating closer to China opens opportunities for the Navy to threaten the Chinese invasion independent of carriers, airfields, Air Force bombers, or long-range missiles.

Offensive and Defensive Mines

Anti-ship mines could be as dangerous (if not more) for the People's Liberation Army as the US and its allies. Taiwan has few beaches and ports suitable for amphibious invasion, making Chinese movements predictable. Hundreds of kilometers of shallow water that are ideal for mines surround China. They are a chaos-inducing weapon because they could delay or destroy Chinese ships, allowing Taiwan to mobilize its military. Mines could also be a way for the US to support Taiwan without committing to a full intervention.

Shallow water! Source

Unfortunately, the US has neglected mines until the last few years. Its inventory (~10,000 mines?) is inadequate and new models are not fully operational. There is also a minelaying capacity issue. Nuclear attack submarines can only carry 20-50 mines. B-1 and B-52 bombers can carry up to 80 smaller mines but may be too valuable and vulnerable to sortie on minelaying. B-2 stealth bombers do not even train for mine-laying missions. Rapid deployment matters because minefields often need thousands of mines to be effective.

There are a few initiatives to correct these issues:

Quickstrike Mines

The Navy recently upgraded its Quickstrike air-launched mine family with modern sensors. These shallow-water mines are conventional bombs with fuses swapped for the mine sensors. The appeal of the Quickstrike mines is that they benefit from air-dropped bomb economies of scale and scope. The cost is low, and manufacturing can ramp quickly. JDAM guidance packages allow aircraft to launch mines from 80 kilometers away. Previously, aircraft had to fly low and slow over the minefield, making them easy targets.

The Air Force may not want to risk its bombers to lay mines, but it might be willing to risk C-130 cargo planes. The Rapid Dragon program is giving them the ability to drop JDAM-equipped bombs. There are enough C-130s to lay entire minefields in one mission, helping to justify the aircraft package of fighters and electronic warfare aircraft required to get the cargo aircraft close enough to drop the mines. There is still a limit to where the Navy and Air Force can realistically deploy these weapons.

Clandestine Delivered Mine

Submarines can deploy mines closer to enemy shores and ports than aircraft. The Navy is upgrading its obsolete submarine mines with the CDM. There are no details about its abilities or operational status.

Hammerhead Mine

Increasing the range that a mine can kill a ship or sub reduces how many mines the Navy needs to lay. The Hammerhead Mine is a system that fires a torpedo at targets, extending its range from meters to kilometers. They would help alleviate the submarine minelaying constraint. The program could reach operational status within the next few years, but rumors suggest production is only thirty units per year. That is not enough to move the needle!

Programmable Mines

Mines used to be indiscriminate. Now they can decipher what kind of ship they are attacking. The next step is to lay them in a dormant state and only activate them at the start of hostilities. Fewer platforms can place mines before a conflict erupts. The Navy has shown interest in this capability, but no known programs are pursuing it.

Mines hold incredible potential for the US Navy, but every initiative needs a 10x multiplier.

Unleashing US Attack Submarines

US attack submarines are feared worldwide. They could wreak havoc on Chinese shipping with torpedos, anti-ship missiles, and mines. But we don't have enough of them. The US Navy deployed ~250 submarines in World War II. The force had little impact before focusing on chokepoints like the Taiwan Strait. The submarine density was too low before the strategy change. The Navy has ~50 attack submarines today. They are more capable but struggle to fulfill all their missions like mine laying, strike, tracking enemy missile submarines, surveillance, and disrupting enemy shipping. And deploying them in shallow water filled with diesel submarines and mines is no one's idea of fun.

The Navy needs previously discussed improvements to minesweeping and submarine detection to reduce the risk of operating subs in Chinese waters. Better weapons can also help submarine survivability. The harpoon missile and Mk-48 torpedos are undergoing incremental upgrades. Torpedos can always be quieter at the start (to avoid giving away the sub's position), faster in the final sprint toward the target, and better at targeting.

The US Navy also needs more submarines if it is serious about minelaying. The Navy and its suppliers seem hesitant to expand production beyond the two shipyards capable of building the beasts. The construction of the new Columbia class nuclear missile submarines further strains the system. Instead, the Navy wants the Orca Extra Large Unmanned Underwater Vehicle (XLUUV). On paper, these are the perfect solution for laying mines. Each copy is supposed to cost less than $50 million and operates without crew, allowing more risk in their mission profile. Their smaller size and lower complexity mean manufacturing time can be short and take place in many shipyards. The program started with high hopes and a successful prototype but is now three years late and hundreds of millions over budget to deliver the first production model. The Navy bought five Orca subs and hopes to have them by the end of 2024.

Energy and payload are related issues when examining the XLUUV mission closer. These subs have diesel-electric powertrains, making them very slow.[1] A round trip to lay mines might take ten days, and they carry fewer mines than a traditional submarine. Even advanced mines like Hammerhead might require 50-100 XLUUVs to be effective. Anduril's Dive LD subsidy could provide some competition and claims costs as low as $30 million per XLUUV. They are still in the honeymoon prototype stage and don't expect the first production version until 2025 (delivered to the Australian Navy). Another option would be to bite the bullet and outfit a few Virginia class subs as dedicated minelayers that can carry 2x-3x the typical payload. It'd take ~40 XLUUVs to match the capacity of one Virginia class minelayer. Manufacturing will have to improve significantly to make XLUUVs practical, and the Navy might still want to convert an existing design to a dedicated minelayer.

The Offensive Summary

$5 billion to buy mines and covert minelayers would create a world-class mine capability and delivery system while freeing up attack subs to put ships on the bottom.

Expanding The Navy's Influence

The purpose of a Navy is to influence events on land. The US Navy's direct impact on land battles will be relatively fleeting except for its aircraft. It has more vertical launch tubes than land attack missiles. Missiles like the Tomahawk aren't ideal weapons for attacking infantry divisions, and many are being converted to anti-ship missiles since Navy cruisers and destroyers have limited organic anti-ship capability. Modern ships have very few guns to bombard land targets with.

The way to impact land battles is fire support with heavier guns.[2] The Navy conducted fire missions in World War II, Korea, Vietnam, and Desert Storm using the 8" and 16" guns on its heavy cruisers and battleships. The firepower of four Iowa class ships would equal ~20% of Taiwan's tube artillery capability and nearly 100% of its highest-performance pieces, even with subcaliber 180-kilometer range shells. Adding modern heavy cruisers would allow the Navy to bring an army worth of artillery to bear for US allies, complete with an efficient seaborne supply chain.

Regaining fire support capability requires a different Navy. It must improve ship procurement and design to avoid disasters like Ford, LCS, and Zumwalt. Ships need some ability to absorb missile hits. Overall, the warships need to be simpler and more specialized. Not every class needs a giant radar or helicopters! These changes will free up the resources to build ships that widen the Navy's capabilities.

The Minimum Viable Navy

The Navy surface fleet is essentially floating airstrips surrounded by air defense batteries. There is only room for ships devoted to carrier operations at today's aircraft carrier costs. Floating airfields are valuable where land bases are constrained or surprise/mobility is critical.

Potential flashpoints with China, like Taiwan or the South China Sea, are more expansive than Europe but aren't the vast Central Pacific. Airfields, aircraft, land-based air defense, and small utility ships can replicate most of a carrier strike group's capabilities in a war with China. Aircraft are capable anti-ship platforms, they can keep enemy airplanes at bay, and there are plenty of airfields to fly from. But they cannot clear the way for supply ships nor operate persistently deep in enemy territory. The minimum viable Navy has to handle enemy mines and submarines. Adding offensive mine and submarine capabilities is the next logical step.

To have more than the minimum navy capability, the US must change how it procures ships, improve the productivity of its shipbuilding industry, and have coherent goals. Carriers can't and shouldn't cost $15 billion, and the weapons and platforms must work.[3] More reasonable carrier costs would allow the fleet to increase in size and add tools to the toolbox. The Navy is just safeguarding the Air Force's packages until then!

The Navy needs a nuclear nano-reactor startup to pivot to small submarine propulsion (manned or unmanned). Having faster small subs with more range would decrease how many need to be purchased compared to a diesel-electric powertrain and could take more load off traditional nuclear attack submarines in domains like intelligence gathering. KRUSTY for subs!

Naval guns vs. rockets like HIMARS fires are a common debate. Ships are great at carrying big, heavy things like giant gun barrels. But it is difficult for them to store and transport lengthy ammunition throughout the ship. That makes guns a good choice. The Navy has used rockets on ships like the LSM-R before they designed their own rockets to have similar dimensions to traditional shells instead of long, skinny Army rockets.

The Forrestal class carriers had similar capabilities to today's carriers but cost <$2.5 billion inflation adjusted dollars. The improved Kitty Hawk class also cost around $2.5 billion in 2022 dollars. Global commercial ship prices have risen slower than CPI inflation over the same time period.

Much of the background for this post was influenced by the Naval Matters Blog. Again, there are few other places like it to learn about and speculate on modern naval warfare.